The Roof of Norway. Home of the Giants. Jotunheimen is arguably the high alpine national park in Norway: From a general plateau of around 1000 m, 80 moutain tops above 2000 m tops shoot up everywhere around you. In Norway, mountain tops 2000 m are considered “high alpine” and collecting 2000 meter peaks, of which there are between 186-386 depending on definition, is not uncommon. All the highest Norwegian mountains are in Jotunheimen, the highest top outside Jotunheimen being Snøhetta, the 26th highest in Norway at 2286 m. Galdhøpiggen, the highest mountain in Norway is 2469 m, Glittertind, the second-highest, and arguably more spectacular is as 2460 m. I have been to both before, but I had not climbed any 2000 m´s on the Norge på Langs, and had looked forward to climbing Mjølkedalstinden in Central Jotunheimen, however the weather prevented that. I did however, meet two guys Koldedalsvatnet aiming to climb Falketind on a day with close to zero visibility. I later saw on a Facebook group that they made it.

For the first time since Knivskjellodden, I experienced genuinely adverse weather: Temperatures around zero, a mix of snow and rain in windy conditions. I struggled to get over Uradalsbandet and ended up spending 30 hours in my tent close to Uradalsvatnet, completely soaked, with water leaking into the tent from below as well. Another reminder, that my excellent lightweight MSR Hubba NX tent is made for pure summer conditions in the Norwegian mountains. I took a calculated risk bringing it as it only weighed 1,3 kg as opposed to the extra kilo for my Hilleberg Soulo, which I increasingly regretted not bringing as autumn carried on. Interestingly, during those 30 hours in the tent, I listened to quite a few podcasts, including an episode ofDNT Utestemmer with Linn Therese Helgesen, at 15, the youngest person to ascend all of Norways 2000+ peaks (377 according to her definition). She is also the daughter of the author of the autoritative book on the subject “Norges fjelltopper over 2000 m”, previously hard to get hold of, but I bought one 3 years ago at Jostedalsbreen national park centre.

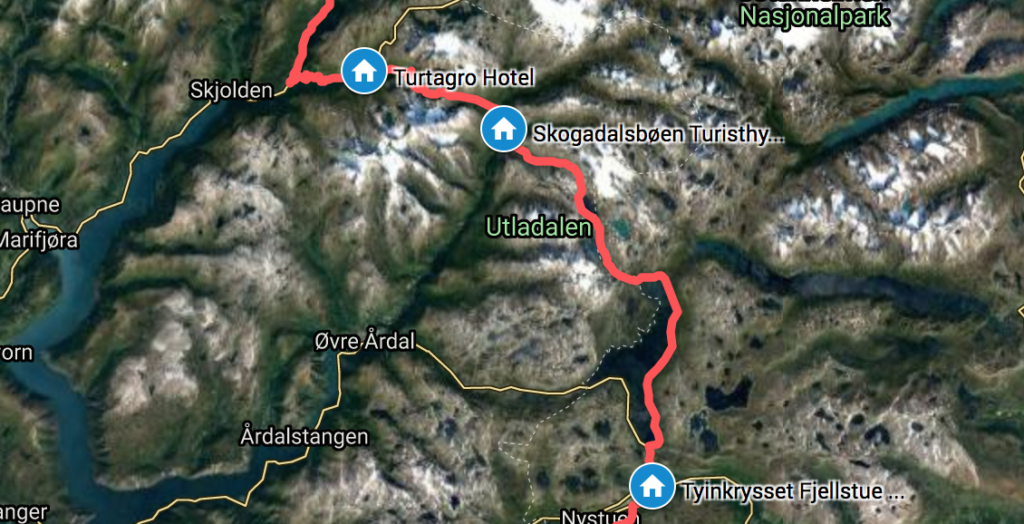

Looking ahead to the next section with mountain passes over 1600 m in Skarvheimen, I started wondering if winter really was coming or not. Accroding to data on senorge.no from the past 5 years the snow falling now would most likely still melt, but you never know. Descending Jotunheimen I passed by Tyinkrysset to resupply and had a chat with the man working in the sports store, and he also was of the opinion that the recent snow would not last.

The only cabin I passed in Jotunheimen was the very popular Skogadalsbøen cabin, but they had chosen to close more than a week before originally announced. Start of september is perhaps the most spectacular time of year in Utladalen, but as I was told, the people walking in the mountains this time of year, school holidays being over, often are not working anymore, and this category of hikers have generally chosen to cancel their trip due to corona. I did not see one single person during my 3-day traverse of Jotunheimen from Turtagrø to Koldedalsvatnet, confirming that not many people are out and about in the mountains now.

I have been to Jotunheimen several times before, including a 3-week round trip in 2016, including tourist magnets such as Galdhøpiggen, Besseggen and Glittertind. For me, the most spectacular area of Jotunheimen is the Centre-West: The area around Olavsbu and down towards Utladalen, an additional reason for me to prefer a more western route in Norge på Langs, as opposed to coming from Røros and then passing through Eastern Jotunheimen. The Centre is quite simply more wild: The mountains seem higher and closer, the valleys deeper and the rivers are wilder, as opposed to the more open geography in the area around Besseggen.

Drem trip #8: A trip around Central Jotunheimen including Mjølkedalstinden and Olavsbu.

Lesson learnt #10: Lightweight 3-season tents are not recommended in the Norwegian mountains, especially not in autumn.